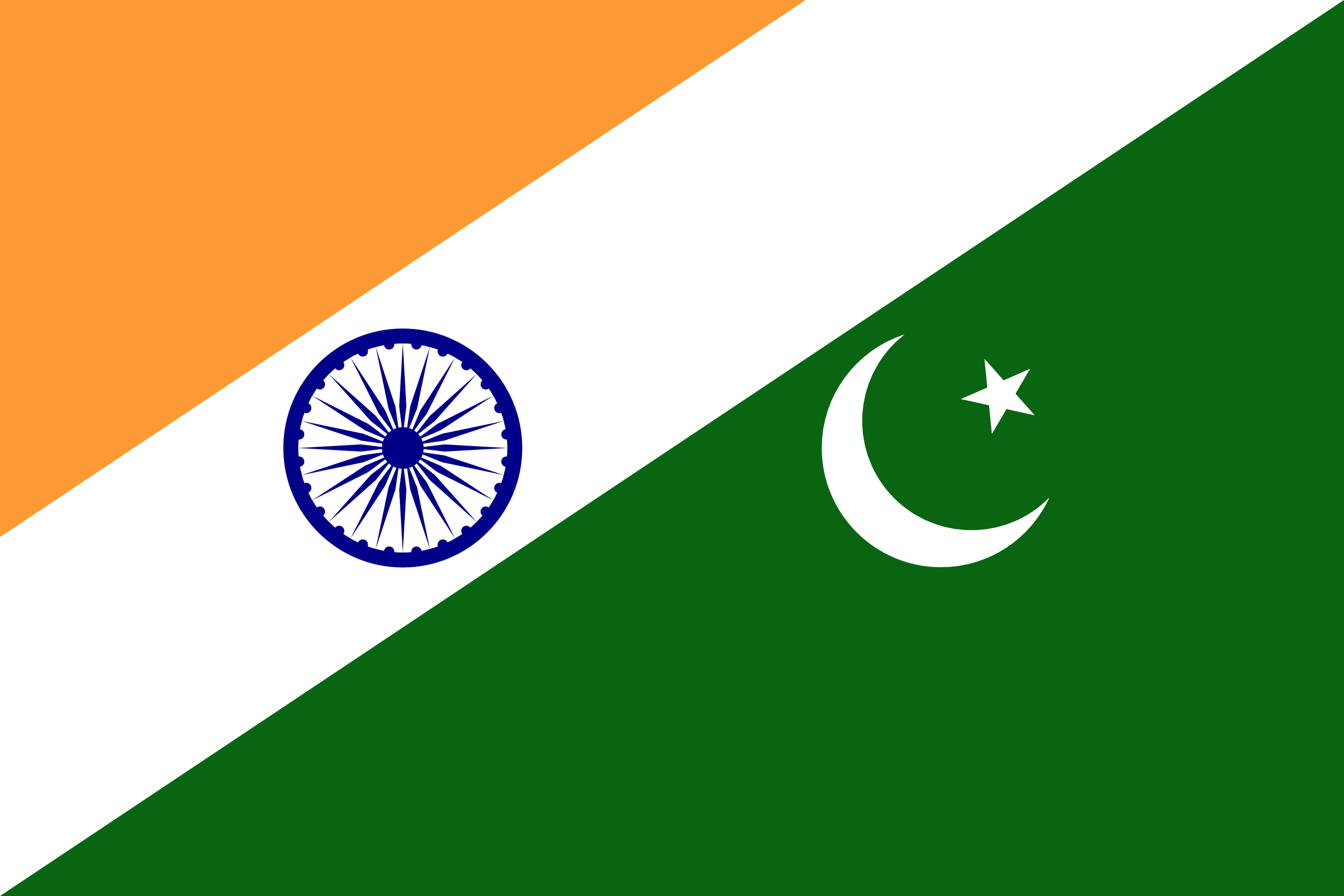

Kashmir: The Vale of Conflict

Basic Facts:

The Kashmir conflict is one of the world’s most intractable territorial disputes, originating in the traumatic 1947 partition of British India into two independent nations on the basis of religions: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, with a Muslim-majority population ruled by a Hindu Maharaja, found itself geographically and politically contested. The Maharaja's decision to accede to India triggered the first Indo-Pakistani war, establishing a de facto partition of the region that persists today. India controls the larger portion, administering it as a union territory (UT) after revoking its special autonomous status in 2019. Pakistan administers a portion in the west, and China holds a smaller territory in the east. This division is fortified by a heavily militarized Line of Control (LoC), marked by frequent skirmishes. The conflict has spawned numerous wars, a persistent insurgency since the late 1980s, severe human rights allegations, and the enduring suffering of the Kashmiri people, who have often been caught in the crossfire of geopolitical ambitions.

Perspectives:

The Kashmiri Narrative: For many Kashmiris, particularly the Muslim majority, the conflict is a struggle for self-determination. The heavy presence of Indian security forces and the 2019 revocation of Article 370, which had granted semi-autonomy to the state, are viewed as acts of occupation, political disenfranchisement, and a threat to cultural identity. Their demands are not monolithic; some seek formal independence, while others advocate for integration with Pakistan. The unifying thread is a desire for agency over their political future; a right they believe was promised upon partition.

The Indian Narrative: India asserts its claim as legal, final, and non-negotiable, based on the Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja. India frames itself as a secular democracy integrating a diverse region, and it portrays the insurgency as Pakistan-sponsored cross-border terrorism that threatens its territorial integrity and national security. Its actions, including the 2019 constitutional changes, are presented as necessary for administrative efficiency, economic development, and ultimate stability.

The Pakistani Narrative: Pakistan grounds its claim in religious nationalism and cultural kinship with Kashmir’s Muslims. It positions itself as the protector of their rights against Indian oppression, highlighting reports of human rights abuses. However, its stance is also driven by strategic interests, including water security from rivers originating in Kashmir and a desire to counter its regional rival, leading international observers to question the sincerity of its advocacy.

Philosophical Approach:

Central Question: Does the principle of self-determination morally outweigh the principle of state sovereignty? This tension lies at the heart of the Kashmir conflict, pitting the post-Westphalian international order, which privileges territorial integrity, against the post-WWI ideal of popular sovereignty.

John Stuart Mill & Self-Determination: Philosophers like Mill argued that freedom is the paramount good and that people are the best guardians of their own interests. From this liberal perspective, a government that rules without the consent of the governed lacks legitimacy. Mill’s concept of liberty would heavily favor the right of the Kashmiri people to determine their own political status through a free and fair plebiscite, a solution once proposed by the UN.

Thomas Hobbes & Sovereignty: Hobbes, in Leviathan, argued that to escape a violent "state of nature," individuals must cede their rights to a sovereign authority in exchange for security and order. The Indian state often employs a Hobbesian rationale, arguing that its sovereignty—however contested—is the sole bulwark against chaos, sectarian violence, and external threat in the region. From this view, upholding state control is the primary moral duty.

Modern International Law: The UN Charter upholds both principles, creating a fundamental ambiguity. While Article 1(2) champions self-determination, Article 2(4) forbids the violation of territorial integrity. This has led to a pragmatic, though often criticized, international stance: state sovereignty is inviolable unless a state collapses or commits gross human rights violations, setting a very high bar for external intervention or support for secession.

Conclusion:

The tragedy of Kashmir is that both sides can appeal to compelling moral principles: one to collective freedom and the other to collective security. The philosophical impasse mirrors the political one, revealing a fundamental flaw in our international system: when a people's desire for sovereignty conflicts with a state's claim to it, there is no clear ethical or legal roadmap to peace.

The Kashmir conflict is one of the world’s most intractable territorial disputes, originating in the traumatic 1947 partition of British India into two independent nations on the basis of religions: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, with a Muslim-majority population ruled by a Hindu Maharaja, found itself geographically and politically contested. The Maharaja's decision to accede to India triggered the first Indo-Pakistani war, establishing a de facto partition of the region that persists today. India controls the larger portion, administering it as a union territory (UT) after revoking its special autonomous status in 2019. Pakistan administers a portion in the west, and China holds a smaller territory in the east. This division is fortified by a heavily militarized Line of Control (LoC), marked by frequent skirmishes. The conflict has spawned numerous wars, a persistent insurgency since the late 1980s, severe human rights allegations, and the enduring suffering of the Kashmiri people, who have often been caught in the crossfire of geopolitical ambitions.

Perspectives:

The Kashmiri Narrative: For many Kashmiris, particularly the Muslim majority, the conflict is a struggle for self-determination. The heavy presence of Indian security forces and the 2019 revocation of Article 370, which had granted semi-autonomy to the state, are viewed as acts of occupation, political disenfranchisement, and a threat to cultural identity. Their demands are not monolithic; some seek formal independence, while others advocate for integration with Pakistan. The unifying thread is a desire for agency over their political future; a right they believe was promised upon partition.

The Indian Narrative: India asserts its claim as legal, final, and non-negotiable, based on the Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja. India frames itself as a secular democracy integrating a diverse region, and it portrays the insurgency as Pakistan-sponsored cross-border terrorism that threatens its territorial integrity and national security. Its actions, including the 2019 constitutional changes, are presented as necessary for administrative efficiency, economic development, and ultimate stability.

The Pakistani Narrative: Pakistan grounds its claim in religious nationalism and cultural kinship with Kashmir’s Muslims. It positions itself as the protector of their rights against Indian oppression, highlighting reports of human rights abuses. However, its stance is also driven by strategic interests, including water security from rivers originating in Kashmir and a desire to counter its regional rival, leading international observers to question the sincerity of its advocacy.

Philosophical Approach:

Central Question: Does the principle of self-determination morally outweigh the principle of state sovereignty? This tension lies at the heart of the Kashmir conflict, pitting the post-Westphalian international order, which privileges territorial integrity, against the post-WWI ideal of popular sovereignty.

John Stuart Mill & Self-Determination: Philosophers like Mill argued that freedom is the paramount good and that people are the best guardians of their own interests. From this liberal perspective, a government that rules without the consent of the governed lacks legitimacy. Mill’s concept of liberty would heavily favor the right of the Kashmiri people to determine their own political status through a free and fair plebiscite, a solution once proposed by the UN.

Thomas Hobbes & Sovereignty: Hobbes, in Leviathan, argued that to escape a violent "state of nature," individuals must cede their rights to a sovereign authority in exchange for security and order. The Indian state often employs a Hobbesian rationale, arguing that its sovereignty—however contested—is the sole bulwark against chaos, sectarian violence, and external threat in the region. From this view, upholding state control is the primary moral duty.

Modern International Law: The UN Charter upholds both principles, creating a fundamental ambiguity. While Article 1(2) champions self-determination, Article 2(4) forbids the violation of territorial integrity. This has led to a pragmatic, though often criticized, international stance: state sovereignty is inviolable unless a state collapses or commits gross human rights violations, setting a very high bar for external intervention or support for secession.

Conclusion:

The tragedy of Kashmir is that both sides can appeal to compelling moral principles: one to collective freedom and the other to collective security. The philosophical impasse mirrors the political one, revealing a fundamental flaw in our international system: when a people's desire for sovereignty conflicts with a state's claim to it, there is no clear ethical or legal roadmap to peace.