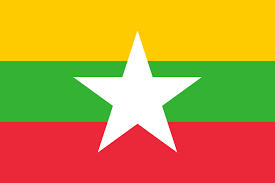

Myanmar: The Rohingya Crisis

Basic Facts:

The crisis facing the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine State is a profound contemporary example of systemic persecution and statelessness. Its roots are deeply embedded in a complex history of colonial legacy, nationalism, and state formation. Following the British annexation of Arakan (now Rakhine State) in 1826, labor migration from the erstwhile Bengal (part of British India) to Burman (the earlier name of Myanmar) was encouraged, altering the region’s demographic fabric. Post-World War II, independence was built on a project of ethnic Burman and Buddhist consolidation. The 1982 Citizenship Law effectively institutionalized the statelessness of the Rohingya by recognizing only ethnic groups that could prove residence before the first Anglo-Burmese War of 1823—a nearly impossible burden of proof for many, especially the Rohingya community.

This legal erasure paved the way for decades of discrimination, restrictions on movement, education, and healthcare, and periodic violence. The catalyst for the current exodus was a series of military “clearance operations” in August 2017, launched in response to attacks by a Rohingya insurgent group. These operations, characterized by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing,” involved mass atrocity crimes, including extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and the burning of hundreds of villages. This forced over 700,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, joining previous waves of refugees in what is now one of the world’s largest refugee camps.

Perspectives:

The State and Majoritarian Narrative: The official position of the Myanmar state and supported by segments of the Bamar Buddhist majority, including some nationalist monastic groups, denies the very existence of the “Rohingya” as a distinct ethnic identity. They are referred to as “Bengalis”—illegal immigrants from Bangladesh who represent a demographic and cultural threat to the Buddhist character of Myanmar. This narrative, often disseminated by state-controlled media, frames the military’s actions as a legitimate response to terrorism and a necessary defense of national sovereignty and social cohesion.

The Rohingya Narrative: The Rohingya people assert an ancient and enduring historical presence in Rakhine State, tracing their community back many centuries. They view themselves as rightful citizens of Myanmar, victims of a state-sponsored project of dehumanization and exclusion. Their narrative is one of profound injustice, persecution, and a desperate plea for recognition, safety, and the restoration of their fundamental rights, including the right to return to their homeland with guarantees of security and citizenship.

International Perspective: The international community, including the United Nations, major human rights organizations, and numerous foreign governments, largely rejects Myanmar’s narrative. Investigations have documented evidence of widespread, systematic human rights violations with genocidal intent. This perspective frames the crisis not as an immigration issue, but as a severe international human rights and humanitarian law emergency, demanding accountability and protection for a vulnerable population.

Philosophical Approach:

Central Question: How can a society reconcile its conception of national identity with the imperative of universal human rights? This tension lies at the heart of the Rohingya crisis, pitting the particularist claims of state sovereignty and cultural preservation against the universalist claims of human dignity.

The Social Contract (Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau): Philosophers of the social contract tradition argue that the state’s legitimacy derives from protecting the rights of those who consent to be governed. From this view, a state that actively strips a population of rights, citizenship, and protection fundamentally breaches its contract. For Locke, the government exists to preserve the “life, liberty, and estate” of its people; a state that becomes the primary threat to these ends forfeits its legitimacy in its dealings with that group.

Kantian Deontology: Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative commands us to act only according to maxims that could become universal law, and to never treat humanity merely as a means to an end. The systemic dehumanization and instrumental use of the Rohingya as a scapegoat for nationalistic unity would be unequivocally condemned by Kantian ethics. It violates the core principle that every individual possesses inherent dignity and must be treated as an end in themselves.

Communitarianism vs. Cosmopolitanism: This modern debate is directly relevant. Communitarians (e.g., Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Sandel) emphasize that individuals are shaped by their community’s traditions and values. They might argue that Myanmar has a right to protect its unique Buddhist cultural and national identity. Cosmopolitans (e.g., Kwame Anthony Appiah), however, would argue that our primary moral obligations transcend national and cultural borders, extending to all human beings by virtue of their shared humanity. They would posit that the Rohingya’s human rights must trump exclusivist national identity projects.

Conclusion:

The Myanmar conflict demonstrates the catastrophic failure to balance these competing values. It presents a stark warning: when a state allows its definition of national identity to necessitate the absolute exclusion and dehumanization of a segment of its people, it commits a fundamental moral failure against both its own ethical traditions and universal human principles.

The crisis facing the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine State is a profound contemporary example of systemic persecution and statelessness. Its roots are deeply embedded in a complex history of colonial legacy, nationalism, and state formation. Following the British annexation of Arakan (now Rakhine State) in 1826, labor migration from the erstwhile Bengal (part of British India) to Burman (the earlier name of Myanmar) was encouraged, altering the region’s demographic fabric. Post-World War II, independence was built on a project of ethnic Burman and Buddhist consolidation. The 1982 Citizenship Law effectively institutionalized the statelessness of the Rohingya by recognizing only ethnic groups that could prove residence before the first Anglo-Burmese War of 1823—a nearly impossible burden of proof for many, especially the Rohingya community.

This legal erasure paved the way for decades of discrimination, restrictions on movement, education, and healthcare, and periodic violence. The catalyst for the current exodus was a series of military “clearance operations” in August 2017, launched in response to attacks by a Rohingya insurgent group. These operations, characterized by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing,” involved mass atrocity crimes, including extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and the burning of hundreds of villages. This forced over 700,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, joining previous waves of refugees in what is now one of the world’s largest refugee camps.

Perspectives:

The State and Majoritarian Narrative: The official position of the Myanmar state and supported by segments of the Bamar Buddhist majority, including some nationalist monastic groups, denies the very existence of the “Rohingya” as a distinct ethnic identity. They are referred to as “Bengalis”—illegal immigrants from Bangladesh who represent a demographic and cultural threat to the Buddhist character of Myanmar. This narrative, often disseminated by state-controlled media, frames the military’s actions as a legitimate response to terrorism and a necessary defense of national sovereignty and social cohesion.

The Rohingya Narrative: The Rohingya people assert an ancient and enduring historical presence in Rakhine State, tracing their community back many centuries. They view themselves as rightful citizens of Myanmar, victims of a state-sponsored project of dehumanization and exclusion. Their narrative is one of profound injustice, persecution, and a desperate plea for recognition, safety, and the restoration of their fundamental rights, including the right to return to their homeland with guarantees of security and citizenship.

International Perspective: The international community, including the United Nations, major human rights organizations, and numerous foreign governments, largely rejects Myanmar’s narrative. Investigations have documented evidence of widespread, systematic human rights violations with genocidal intent. This perspective frames the crisis not as an immigration issue, but as a severe international human rights and humanitarian law emergency, demanding accountability and protection for a vulnerable population.

Philosophical Approach:

Central Question: How can a society reconcile its conception of national identity with the imperative of universal human rights? This tension lies at the heart of the Rohingya crisis, pitting the particularist claims of state sovereignty and cultural preservation against the universalist claims of human dignity.

The Social Contract (Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau): Philosophers of the social contract tradition argue that the state’s legitimacy derives from protecting the rights of those who consent to be governed. From this view, a state that actively strips a population of rights, citizenship, and protection fundamentally breaches its contract. For Locke, the government exists to preserve the “life, liberty, and estate” of its people; a state that becomes the primary threat to these ends forfeits its legitimacy in its dealings with that group.

Kantian Deontology: Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative commands us to act only according to maxims that could become universal law, and to never treat humanity merely as a means to an end. The systemic dehumanization and instrumental use of the Rohingya as a scapegoat for nationalistic unity would be unequivocally condemned by Kantian ethics. It violates the core principle that every individual possesses inherent dignity and must be treated as an end in themselves.

Communitarianism vs. Cosmopolitanism: This modern debate is directly relevant. Communitarians (e.g., Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Sandel) emphasize that individuals are shaped by their community’s traditions and values. They might argue that Myanmar has a right to protect its unique Buddhist cultural and national identity. Cosmopolitans (e.g., Kwame Anthony Appiah), however, would argue that our primary moral obligations transcend national and cultural borders, extending to all human beings by virtue of their shared humanity. They would posit that the Rohingya’s human rights must trump exclusivist national identity projects.

Conclusion:

The Myanmar conflict demonstrates the catastrophic failure to balance these competing values. It presents a stark warning: when a state allows its definition of national identity to necessitate the absolute exclusion and dehumanization of a segment of its people, it commits a fundamental moral failure against both its own ethical traditions and universal human principles.