Northern Ireland: The Politics of Belonging (Historical)

Basic Facts:

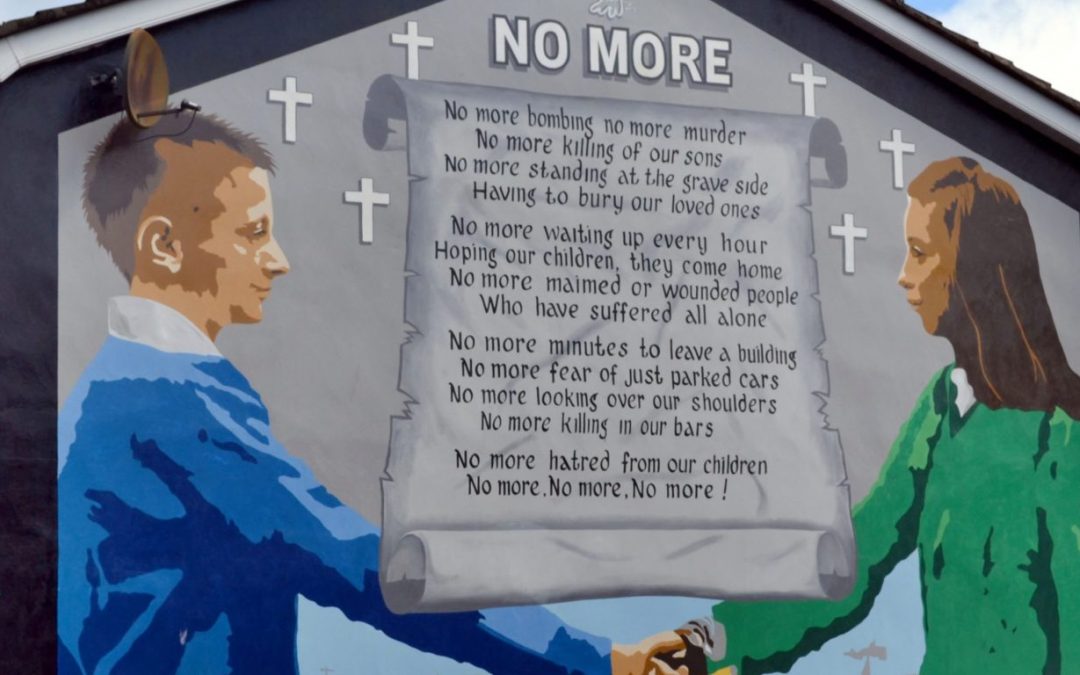

Known as The Troubles (c. 1968-1998), the conflict in Northern Ireland was a protracted, low-intensity war fought over national sovereignty and the right to belong. Its roots stretch back to the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century, when the British crown settled Protestant Scots and English on land confiscated from Gaelic Irish Catholics, creating a demographic and political schism that would define the region. The modern conflict erupted from the civil rights movement of the late 1960s, where the Catholic minority protested systemic discrimination in housing, employment, and voting (gerrymandering). The violent suppression of these peaceful marches and the descent into inter-communal violence led to the deployment of the British Army, the resurgence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and the mobilization of loyalist paramilitaries. For three decades, the region was scarred by sectarian killings, bombings, and political deadlock. The conflict was formally concluded by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, a monumental achievement in conflict resolution that established a power-sharing government, recognized the right to both British and Irish identities, and committed to the disarmament of paramilitary groups. While peace walls still physically divide communities and political tensions periodically flare, the Good Friday Agreement stands as a powerful testament to the possibility of ending entrenched violence through dialogue and compromise.

Perspectives:

The Nationalist (or, the predominantly Catholic) Narrative: For many in the Catholic community, the state of Northern Ireland was founded on a premise of injustice—a Protestant-dominated polity designed to exclude them. Their struggle was initially for civil rights within the UK but evolved into a national liberation struggle against what was perceived as a foreign occupation. Their Catholic faith was less a driver of violence than a core component of a besieged cultural identity, intertwined with a historical narrative of colonial dispossession and a yearning for reunification with the Republic of Ireland.

The Unionist (or, the predominantly Protestant) Narrative: The Unionist community viewed itself as British citizens defending their homeland against a terrorist campaign aimed at forcing them into a united Ireland against their will. Their Protestant faith was inextricably linked to their British identity, representing a heritage of civil and religious liberty dating back to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. They feared becoming a persecuted minority in a Catholic-dominated state, an anxiety rooted in historical sieges and a deep-seated need to preserve their cultural and political way of life.

The Mediating Perspective: The British and Irish governments, along with neutral parties like the United States of America, eventually came to see the conflict not as a fight against terrorism nor an anti-colonial struggle, but as a tragic inter-communal conflict between two legitimate identities. This shift was essential for the peace process, recognizing that both communities had legitimate fears, aspirations, and a right to exist securely within Northern Ireland.

Philosophical Analysis:

Central Question: When political and religious identities become fused into a single, oppositional force, can they be deliberately disentangled to create a new, shared political identity? Northern Ireland’s story is not just one of conflict but of a courageous, ongoing experiment in answering this question affirmatively. The peace process demonstrates that while these identities are deeply intertwined, they are not immutable.

Hegel's Dialectic and Synthesis: The conflict can be viewed through a Hegelian lens as a struggle between two competing claims to truth and recognition (thesis and antithesis). For decades, each side sought the total negation of the other. The Good Friday Agreement, however, represents a profound synthesis. It did not choose one identity over the other but created a new political framework that contained both. It acknowledged the legitimacy of both the British and Irish constitutional preferences and allowed individuals to choose their own national identity. This was a philosophical masterstroke: it transcended the zero-sum game by refusing to validate one narrative at the expense of the other.

John Rawls and Overlapping Consensus: Political philosopher John Rawls argued that a stable society requires an “overlapping consensus” where citizens with different comprehensive doctrines (e.g., religious worldviews) can agree on a set of political principles for the basic structure of society. The Good Friday Agreement is a practical embodiment of this theory. It did not require Protestants and Catholics to agree on theology, history, or even their ultimate national aspiration. It only required them to agree on the rules of the game: the renunciation of violence, the principle of consent, and the mechanics of power-sharing. They could remain devoutly Unionist or Nationalist in their private identities while consenting to a shared public space.

Jürgen Habermas and Communicative Action: German philosopher Jürgen Habermas’s theory of communicative action—where mutual understanding is reached through reasoned dialogue free from coercion—provides a model for the peace process. The negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement involved painstaking, often frustrating dialogue that forced each side to listen to the core fears of the other. This process did not erase differences but created a space where former enemies could recognize each other not as abstract monsters, but as human beings with legitimate grievances.

Conclusion:

The lesson of Northern Ireland is not that deep-seated identity conflicts have easy solutions, but that they can be managed. The Good Friday Agreement did not solve the problem; it designed a container sturdy enough to hold the conflict without violence. It proves that political creativity can build frameworks where opposing sacred identities can coexist, not in passive harmony, but in a productive but tense equilibrium. It stands as a beacon to the world that even the most intractable conflicts can be ended not by the victory of one side, but by the wisdom to stop demanding victory altogether.

Known as The Troubles (c. 1968-1998), the conflict in Northern Ireland was a protracted, low-intensity war fought over national sovereignty and the right to belong. Its roots stretch back to the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century, when the British crown settled Protestant Scots and English on land confiscated from Gaelic Irish Catholics, creating a demographic and political schism that would define the region. The modern conflict erupted from the civil rights movement of the late 1960s, where the Catholic minority protested systemic discrimination in housing, employment, and voting (gerrymandering). The violent suppression of these peaceful marches and the descent into inter-communal violence led to the deployment of the British Army, the resurgence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and the mobilization of loyalist paramilitaries. For three decades, the region was scarred by sectarian killings, bombings, and political deadlock. The conflict was formally concluded by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, a monumental achievement in conflict resolution that established a power-sharing government, recognized the right to both British and Irish identities, and committed to the disarmament of paramilitary groups. While peace walls still physically divide communities and political tensions periodically flare, the Good Friday Agreement stands as a powerful testament to the possibility of ending entrenched violence through dialogue and compromise.

Perspectives:

The Nationalist (or, the predominantly Catholic) Narrative: For many in the Catholic community, the state of Northern Ireland was founded on a premise of injustice—a Protestant-dominated polity designed to exclude them. Their struggle was initially for civil rights within the UK but evolved into a national liberation struggle against what was perceived as a foreign occupation. Their Catholic faith was less a driver of violence than a core component of a besieged cultural identity, intertwined with a historical narrative of colonial dispossession and a yearning for reunification with the Republic of Ireland.

The Unionist (or, the predominantly Protestant) Narrative: The Unionist community viewed itself as British citizens defending their homeland against a terrorist campaign aimed at forcing them into a united Ireland against their will. Their Protestant faith was inextricably linked to their British identity, representing a heritage of civil and religious liberty dating back to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. They feared becoming a persecuted minority in a Catholic-dominated state, an anxiety rooted in historical sieges and a deep-seated need to preserve their cultural and political way of life.

The Mediating Perspective: The British and Irish governments, along with neutral parties like the United States of America, eventually came to see the conflict not as a fight against terrorism nor an anti-colonial struggle, but as a tragic inter-communal conflict between two legitimate identities. This shift was essential for the peace process, recognizing that both communities had legitimate fears, aspirations, and a right to exist securely within Northern Ireland.

Philosophical Analysis:

Central Question: When political and religious identities become fused into a single, oppositional force, can they be deliberately disentangled to create a new, shared political identity? Northern Ireland’s story is not just one of conflict but of a courageous, ongoing experiment in answering this question affirmatively. The peace process demonstrates that while these identities are deeply intertwined, they are not immutable.

Hegel's Dialectic and Synthesis: The conflict can be viewed through a Hegelian lens as a struggle between two competing claims to truth and recognition (thesis and antithesis). For decades, each side sought the total negation of the other. The Good Friday Agreement, however, represents a profound synthesis. It did not choose one identity over the other but created a new political framework that contained both. It acknowledged the legitimacy of both the British and Irish constitutional preferences and allowed individuals to choose their own national identity. This was a philosophical masterstroke: it transcended the zero-sum game by refusing to validate one narrative at the expense of the other.

John Rawls and Overlapping Consensus: Political philosopher John Rawls argued that a stable society requires an “overlapping consensus” where citizens with different comprehensive doctrines (e.g., religious worldviews) can agree on a set of political principles for the basic structure of society. The Good Friday Agreement is a practical embodiment of this theory. It did not require Protestants and Catholics to agree on theology, history, or even their ultimate national aspiration. It only required them to agree on the rules of the game: the renunciation of violence, the principle of consent, and the mechanics of power-sharing. They could remain devoutly Unionist or Nationalist in their private identities while consenting to a shared public space.

Jürgen Habermas and Communicative Action: German philosopher Jürgen Habermas’s theory of communicative action—where mutual understanding is reached through reasoned dialogue free from coercion—provides a model for the peace process. The negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement involved painstaking, often frustrating dialogue that forced each side to listen to the core fears of the other. This process did not erase differences but created a space where former enemies could recognize each other not as abstract monsters, but as human beings with legitimate grievances.

Conclusion:

The lesson of Northern Ireland is not that deep-seated identity conflicts have easy solutions, but that they can be managed. The Good Friday Agreement did not solve the problem; it designed a container sturdy enough to hold the conflict without violence. It proves that political creativity can build frameworks where opposing sacred identities can coexist, not in passive harmony, but in a productive but tense equilibrium. It stands as a beacon to the world that even the most intractable conflicts can be ended not by the victory of one side, but by the wisdom to stop demanding victory altogether.